A contribution by C Companyero, inspired by CrimethInc

The opposite of direct action is representation. There are many kinds of representation—words are used to represent ideas and experiences, the viewers of a TV show let their own hopes and fears be represented by those of the characters,—but the most well-known example today can be found in the electoral system. In this society, we’re encouraged to think of voting as our primary means of exercising power and participating socially. Yet whether one votes with a ballot for a politician’s representation, with kwachas for a corporate product, or with one’s wardrobe for a certain culture, voting is an act of deferral, in which the voter picks a person or system or concept to represent her interests. This is an unreliable way to exercise power.

Let’s compare voting with direct action, to bring out the differences between mediated and unmediated activity in general. Voting is a lottery: if a candidate doesn’t get elected, then the energy his constituency put into supporting him is wasted, as the power they were hoping he would exercise for them goes to someone else. With direct action, one can be certain that one’s work will offer results. In marked contrast to every kind of petitioning, direct action secures resources that others can never take away: experience, contacts in the community, the grudging respect of adversaries.

Voting consolidates the power of a whole society in the hands of a few individuals; through sheer force of habit, not to speak of other methods of enforcement, everyone else is kept in a position of dependence. In direct action, people utilize their own resources and capabilities, discovering in the process what these are and how much they can accomplish.

Voting forces everyone in a movement to try to agree on one platform: coalitions fight over what compromises to make, each faction insisting that its way is the best and that the others are messing everything up by not going along with its program. A lot of energy gets wasted in these disputes and recriminations. In direct action, no vast consensus is necessary: different groups apply different tactics according to what they believe in and feel comfortable doing, with an eye to complementing one another’s efforts. People involved in different direct actions have no need to squabble, only if they really are seeking conflicting goals, or years of voting have taught them to fight with anyone who doesn’t think exactly as they do.

Conflicts over voting often distract from the real issues at hand, as people get caught up in the drama of one party against another, one candidate against another. With direct action, the issues themselves are raised, addressed specifically, and often resolved.

Voting is only possible when election time comes around. Then you are told to shut up for 5 years. Direct action can be applied whenever one sees fit. Voting is only useful for addressing topics that are currently on the political agendas of candidates, while direct action can be applied in every aspect of your life, in every part of the world you live in. Direct action is a more efficient use of resources than voting, campaigning, or canvassing: an individual can accomplish with one kwacha a goal that would cost a collective a thousand kwacha, a non-governmental organization a million kwacha, a corporation a ten million kwacha, and the government a billion kwacha.

Voting is glorified as a manifestation of our supposed freedom. It’s not freedom— freedom is getting to decide what the choices are in the first place, not picking between Fanta Orange and Fanta Pineapple. Direct action is the real thing. You make the plan, you create the options, the sky’s the limit.

Ultimately, there’s no reason the strategies of voting and direct action can’t both be applied together. One does not cancel the other out. The problem is that so many people think of voting as their primary way of exerting political and social power that a disproportionate amount of time and energy is focused on electoral affairs while other opportunities to make change go to waste. For months and months preceding every election, everyone argues about the voting issue, what candidates to vote for or whether to vote at all, when voting itself takes less than a day. Vote or don’t, but get on with it! Remember all the other ways you can make your voice heard.

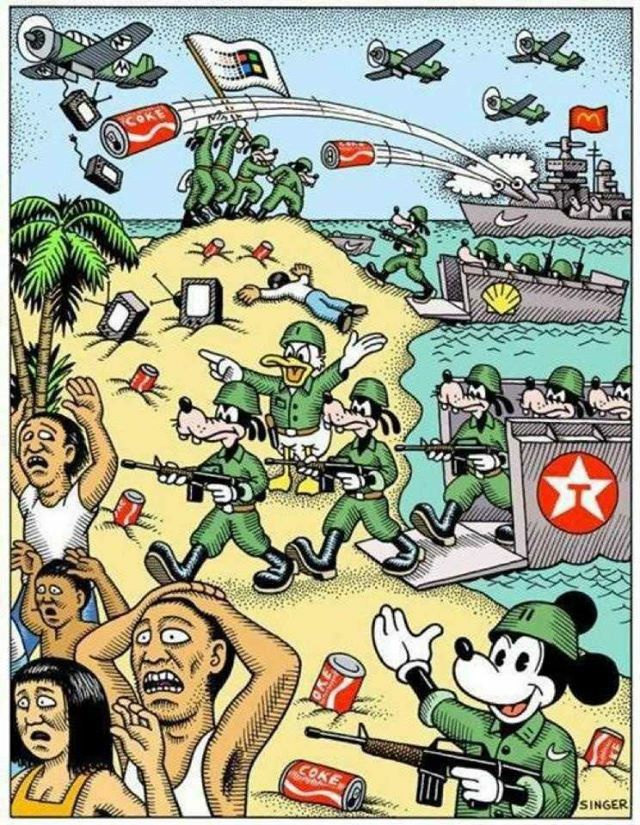

Hegemony (cultural domination ) includes social class; hence, the philosophic and sociologic theory of cultural hegemony analyses the social norms that establish the social structures (social and economic classes) with which the ruling class establish and exert cultural dominance to impose their world view—justifying the social, political, and economic status quo—as natural, inevitable, and beneficial to every social class, rather than as the artificial social constructs defined by and beneficial solely to the ruling class.

Hegemony (cultural domination ) includes social class; hence, the philosophic and sociologic theory of cultural hegemony analyses the social norms that establish the social structures (social and economic classes) with which the ruling class establish and exert cultural dominance to impose their world view—justifying the social, political, and economic status quo—as natural, inevitable, and beneficial to every social class, rather than as the artificial social constructs defined by and beneficial solely to the ruling class.

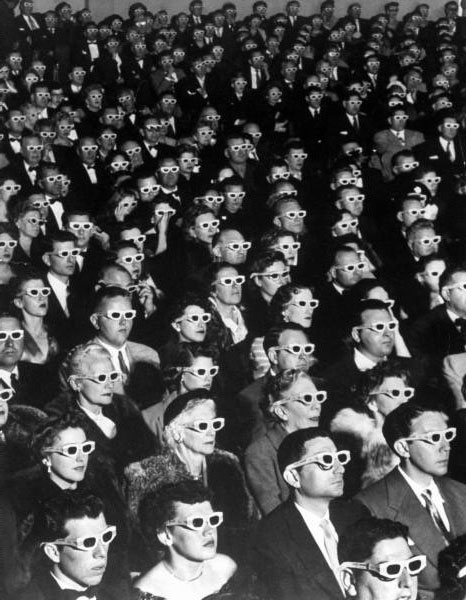

“reality shows”, far off sports events, or celebrity news. All this is used to replace authentic experiences we miss because of our alienation from our work and life. In the village life is hard, but there is a clear connection between the activity of the farmer and the product, especially when it is subsistence farming. On the other hand the city dweller is alienated from her food, and spends time in pursuit of money which is used to buy products from which the history is unknown. The rich do not experience life, they hide behind walls with electricity on top or razor wire. They collect imported products that give no real experience and no real satisfaction. In an air-conditioned vehicle the passenger does not experience the surroundings. The MP avoids his constituency, the rich drink imported liquor and use private guards to keep away the population.

“reality shows”, far off sports events, or celebrity news. All this is used to replace authentic experiences we miss because of our alienation from our work and life. In the village life is hard, but there is a clear connection between the activity of the farmer and the product, especially when it is subsistence farming. On the other hand the city dweller is alienated from her food, and spends time in pursuit of money which is used to buy products from which the history is unknown. The rich do not experience life, they hide behind walls with electricity on top or razor wire. They collect imported products that give no real experience and no real satisfaction. In an air-conditioned vehicle the passenger does not experience the surroundings. The MP avoids his constituency, the rich drink imported liquor and use private guards to keep away the population.

crambling to eat and find shelter from the elements. The rich are scrambling for more and more material possessions. The latest model cell phone, a more expensive car from a more exclusive brand for a more exclusive price. And many liters of fuel free per month. You name it. Does this unbalance make our society better?

crambling to eat and find shelter from the elements. The rich are scrambling for more and more material possessions. The latest model cell phone, a more expensive car from a more exclusive brand for a more exclusive price. And many liters of fuel free per month. You name it. Does this unbalance make our society better?

Power comes in two flavours:

Power comes in two flavours:

power-over that infringes on our quality of life. The power-over is the type of power that rules strongly in the patriarchy, the arbitrary power that corrupts life and keeps Malawi from being developed.

power-over that infringes on our quality of life. The power-over is the type of power that rules strongly in the patriarchy, the arbitrary power that corrupts life and keeps Malawi from being developed.

for a new purpose. In the days of the Cold War the International Aid was used to secure a position of power opposite the other party (USA/NATO vs. Soviet Union/Warsaw Pact). Now it was used by western powers to secure their economic position and to prevent failed states. Failed states are a problem: from Afghanistan the terrorists flew into the New York World Trade Center and the Washington Pentagon, for the coast of Somalia pirates are stealing ships, from Syria refugees are feeling into Europe, and more of such issues. So rich countries have an interest to prevent failed states; that is cheaper than dealing with the consequences.

for a new purpose. In the days of the Cold War the International Aid was used to secure a position of power opposite the other party (USA/NATO vs. Soviet Union/Warsaw Pact). Now it was used by western powers to secure their economic position and to prevent failed states. Failed states are a problem: from Afghanistan the terrorists flew into the New York World Trade Center and the Washington Pentagon, for the coast of Somalia pirates are stealing ships, from Syria refugees are feeling into Europe, and more of such issues. So rich countries have an interest to prevent failed states; that is cheaper than dealing with the consequences. the IMF on the FISP and this anti-liberal policy was successful. We see how the IMF has the interests of its donors in mind (the biggest donor is the capitalist USA) and not ours. For a long account on this kind of policies read “Confessions of an economic hit man by Perkins, free to download

the IMF on the FISP and this anti-liberal policy was successful. We see how the IMF has the interests of its donors in mind (the biggest donor is the capitalist USA) and not ours. For a long account on this kind of policies read “Confessions of an economic hit man by Perkins, free to download

tion” and “violence” not as the single hidden truth of the world but as immanent principles, as equal constituents of any social reality, they can reveal a great deal one would not be able to see otherwise. For one thing, everywhere, imagination and violence seem to interact in predictable, and quite significant, ways. Let’s start with a few words on violence, providing a very schematic overview of arguments:

tion” and “violence” not as the single hidden truth of the world but as immanent principles, as equal constituents of any social reality, they can reveal a great deal one would not be able to see otherwise. For one thing, everywhere, imagination and violence seem to interact in predictable, and quite significant, ways. Let’s start with a few words on violence, providing a very schematic overview of arguments:

With Presdent Mutharika’s background as a law Professor we cannot attribute this delay to ignorance: he knows that the law does not prescribe other laws to be amended before implementation. It is simply delay tactics. This is contradicting the manifesto we elected him on, and it should not be done like this. Presdent Mutharika should show that he is a trustworthy politician, and

With Presdent Mutharika’s background as a law Professor we cannot attribute this delay to ignorance: he knows that the law does not prescribe other laws to be amended before implementation. It is simply delay tactics. This is contradicting the manifesto we elected him on, and it should not be done like this. Presdent Mutharika should show that he is a trustworthy politician, and  implement the manifesto. How do we know who to vote for if the manifesto is not being followed? That is not democracy, that is deceiving the population.

implement the manifesto. How do we know who to vote for if the manifesto is not being followed? That is not democracy, that is deceiving the population.